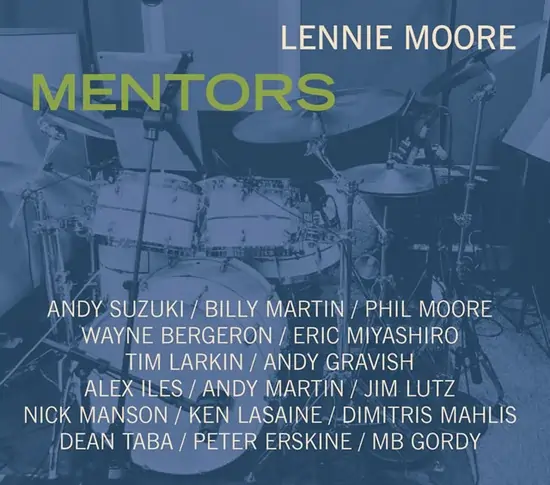

Mentors

This album is available digitally for listening or purchase at all of your favorite spaces.

Introductions

I've wanted to do a big band album for a long time...literally decades! Several years ago I was thinking back on all the mentors I’ve had in my life who helped to shape or influence who I am as a composer and artist. And I just felt so grateful for each of them, in their own ways, spending time and energy with a young musician sharing their knowledge and wisdom.

I've been thinking a lot about the importance of mentors, the master-apprentice relationship, and how art advances through the ages on a continuum of community. This is at the heart of why I mentor young composers and it’s the core concept for this album.

Each track on this album is dedicated to someone who was a mentor or major influence in my life. Their teaching, advice, critiques, philosophies, support, and encouragement all made major impacts toward developing my own aesthetics about my craft and the creative decisions I make every day. For some of these influences it was simply their body of work and the inspiration it gave me to do what I do.

Every composition on this album is my tribute to them. With each work, I’ve reflected on who they are, what they taught me, and elements of their artistry that were inspirational. In my arrangements I’ve played with form, texture, melody, and harmony - developing something that pushes the boundaries of typical big band writing, which I hope you will enjoy.

This album is dedicated to them, and to mentors everywhere.

About the mentors statements on this page...

The idea of putting together this collection of statements on mentorship from me, the people to whom this album is dedicated to, and the musicians who performed on it came out of a private text communication I had with Michael Gibbs in the fall of 2018. I had asked him to come up with a few paragraphs on who his mentors were and how they influenced his life as an artist. As with everyone involved with this album, we were all dealing with busy schedules so I let him know to get this to me whenever he could. I was in the middle of writing the compositions for this project myself.

In early December, about two months after our previous conversation, I got an amazing extended response from Michael that pretty much was an equivalent to the history of jazz in America! Keep in mind how big the chat windows are with social media platforms (usually three to four words per line) and you can imagine my laughter and joy in seeing this massive tome.

Even though I had only asked for 1-2 paragraphs, what Michael sent to me made me completely rethink what this project was about. This is typical of my experience with Michael as a mentor. He always made me consider things on a deeper and more profound level. Instead of just making an album dedicated to those who influenced my life as an artist, I started to think, “F$*%! Now I have to create a foundation on mentorship!”

At the time, seeing this statement filled me with so much emotion that I teared up, thinking about the gifts I’ve received over the years from special people like Michael Gibbs, Weather Report/Steps Ahead, Peter Erskine, Arif Mardin, Don Grolnick, David Mash, Nick Manson, Andy Suzuki, Ken Kraintz, and Toshiko Akiyoshi. They have contributed to my development as an artist in more ways than I can express. As a young musician learning my craft and discovering what my spot was going to be in this universe, I feel nothing but gratefulness and love for what these extraordinary souls have been to me.

— Lennie Moore

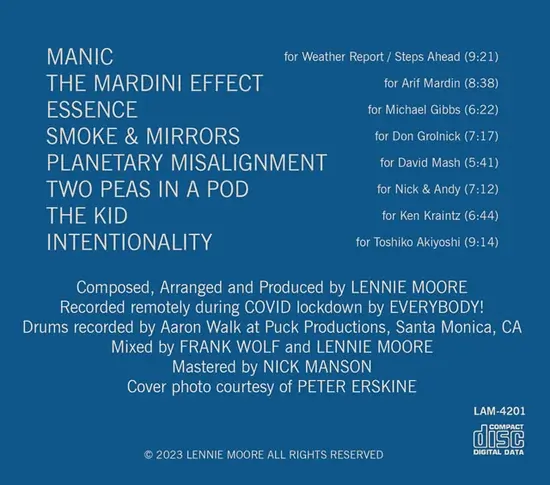

Manic

for Weather Report / Steps Ahead

For years, I was always the young person in the band (and usually the youngest). This meant that most anyone in the group could assume the mantle of being the mentor. Some were wiser and more experienced than others. Advice ranged from “Be sure to listen to every kind of music” (Johnny Richards), to “You’re a nice kid, but you can’t swing for shit” (Nat Pierce). My favorite words of wisdom came from my teacher George Gaber, who taught me to, “discover (my) own long-lasting musical values,” in addition to practical hands-on lessons involving tone and touch. Joe Zawinul taught me to put any and all body movement/energy into what I was playing, as well as to always compose when I play.

Sadao Watanabe taught me a lovely Japanese expression, “Ichi go, ichi ye (ee-chee go, ee-chee yay),” and that translates roughly to “Today is the first time we meet, and today might be the last time that we meet.” It is, perhaps, a uniquely Japanese sentiment, but it has application to all who might be open to its meaning. An encounter with another being, whether on a musical or personal level, is a fleeting moment in time. Its beauty lies in the transient nature of its passage in time. And yet, we all know that such fleeting moments leave a taste in the memory that can be quite evocative. And so, reasoning would have it, why not make the very most out of every chance we have to interact with another, musically or otherwise? Put another way: life is too short not to have fun.

And so now, I pass along these very same messages save for the Nat Pierce sentiment. Old school and tough love, but I’m a university professor now … The one thing I can tell you about how my drumming has changed over the years: when I was younger, I played as if my own life depended on it. Now, I play as if someone else’s life depends on it.

— Peter Erskine

I was in high school when I first heard Weather Report’s Heavy Weather album. It blew my mind as to what was (at that time) a contemporary jazz sound and feel. And the bass performances by Jaco Pastorius - Wow!!

I didn’t discover until later that their approach was innovative, where every member could partake in lead or supporting roles: Jaco could play the melody while Wayne Shorter covered with an accompaniment, or a bass figure! Jaco would play a guiding line behind Wayne’s soloing, while Joe Zawinul played bass lines on synth. Alex Acuña’s great drumming and Manolo Badrena’s percussion drove excitement into every track, and the compositions, harmonic language and solos have always floored me.

In subsequent albums, Victor Bailey and Omar Hakim put their indelible stamp on my favorite albums with their wonderful playing. Peter Erskine, especially, has continuously inspired me with what he creates in every moment of his performances, and is the main thread connecting Weather Report and my other favorite band, Steps Ahead. Those amazing performances with Mike Manieri, Michael Brecker, Eddie Gomez, Eliane Elias, and Don Grolnick, along with compositions by Peter, the Michael’s, and Don have always been some of my favorites.

Over the years, I’ve had the honor of knowing and hanging occasionally with Peter. He’s such a terrific person. His playing is so wonderfully nuanced. There are times where he totally surprises me with something explosive! I don’t know where it comes from, but I love it and can’t get enough.

One of the things that makes me smile and feel very connected with him is that we’re both kind of nerds (this is a high compliment). As a kid, I grew up feeling like a bit of an alien, except for some of my nerdy friends, and being a part of some composing workshops in high school (which I’ll touch on later, when I talk about Centrum). Somehow, I knew deep inside, that creating and expressing myself through music was a special thing. Feeling connected with artists like Peter reinforces this knowledge that we eventually find our peeps, and I recognize through his example that continually working on improving your craft, listening, being curious, and learning every day is an exceptional life.

Peter’s mentorship, for me, has been in his performances, our conversations, and his sage advice, which continues with his contributions on this project. I’m so appreciative of his time (no pun intended!) and wisdom.

Manic is honestly a bit of a bi-polar composition. The title is derived from two feels: the more chill bossa feel in the Primary section, and the hyper-crazed and blistering be-bop Secondary section. These two contrasting sections provide a fun arrangement to solo over, while the horns have some very challenging Zappa-esque lines to blast through. The harmonic language is based on shifting sets of chords, much like Don Grolnick’s Four Chords from the Steps album Paradox.

The track starts off with Andy Suzuki on Tenor Sax and Nick Manson on Piano, as an introduction designed to bring the listener into the album experience. It serves as a raising-of-the-curtain and prefaces the improvised solos that Andy and Nick perform so beautifully later in the piece.

After the intro, Ken Lasaine enters with four syncopated chords that establish the Primary section, slowly building as MB Gordy enters with percussion, followed by me on electric bass and Nick on Fender Rhodes. Peter Erskine’s drumming propels this whole track forward, and his soloing is brilliant throughout.

After Peter and Andy rip through their solos, the shout chorus kicks into high gear as Wayne Bergeron and Eric Miyashiro power through their “scream” registers and take us home.

— Lennie Moore

The Mardini Effect

for Arif Mardin

In addition to his status as a legendary producer and arranger, Arif Mardin (my father) was famous (perhaps just a little infamous) for his Mardini: a drier than dry, some have said lethal vodka martini, served straight up with olive. Lennie, in titling his tribute to Arif, “The Mardini Effect” is of course playing on a double meaning: one the ‘effect’ of imbibing this potent elixir, prepared for you by this elegant gentleman in the perfect, chilled glass and the other meaning of course, as Lennie said to me is the effect of Arif’s “music production and ability to find the magic in each artist's voice.”

When I heard the first sketches of Lennie’s “The Mardini Effect,” it was evident inspiration had come from the “Suite Fraternidad,” Arif’s 1993 two-movement jazz and flamenco piece for the WDR big band with strings and soloists (premiered with an introduction by my father’s dear friend, Quincy Jones at the Montreux Jazz Festival). That the Suite could come from the pen of a composer whose first musical loves and greatest influences were Duke Ellington, Stravinsky, Charlie Parker and Bela Bartok among others is more than plausible but the other dimension is of course that said composer was essentially ‘moonlighting’ from his ‘day job’ as a Grammy winning producer and arranger of some the most iconic hits of the 20th into the 21st centuries (while also a Senior Vice President of a major Record label). I think Lennie also sees this dual existence as part of ‘the effect.’

So of course Lennie and I share being influenced by Arif’s string and horn arrangements for ‘pop’ records. His charts always struck just the right balance, at once completely supportive of the artist and the song while also musically meaningful and bold when called for. His arrangements would never distract but never were they musical wallpaper either. His signature, Lalah Hathaway said is like a “watermark.”

Perhaps another ‘effect' Lennie is alluding to becomes evident upon being able to listen to Arif’s ‘sweetening’ on its own; passages integral to the record are revealed as autonomous little compositions. As an arranger, I strive for the same goal and one can hear, for instance, in Lennie’s epic, orchestral scores for video games that he is faithfully serving the game but with music that stands on its own.

Lennie commenced this album as a collection of homages and I think Arif would have observed, ‘you took inspiration from your mentors but you made the music your own!’ Perhaps that’s the true ‘effect.’

Lennie, you would have been invited for Mardinis.

— Joe Mardin

I first met Arif Mardin during my graduation ceremony at Berklee College of Music in Boston in 1983. I was receiving my diploma after completing a four-year degree in Jazz Composition. As the guest speaker and recipient of an Honorary Doctorate alongside Quincy Jones, he shook my hand with the biggest smile on his face. I don’t think that smile was particularly directed at me. It was just the way he was with everybody – Joy, personified.

Having two of my heroes for Music Production and Arranging sharing their wisdom at my graduation was a gift. I had been listening to their inspiring work for years, dissecting every moment of every track from my favorite albums, trying to glean some understanding of how to make great records. What I believe they taught me was how something sounded when it was right, when all the elements would come together, from the musicians’ performances, to what you needed to have happening to be able to capture it during recording, to the mixing and mastering processes. The choice of microphones, the room you record in, the mixing console, the recording engineer, the arrangements, what you say to the players to coax a great performance – they all contribute to the result which, if you do your job well, can be profound. It is that perfect blend of the composition, and the presentation of the work, as it comes out of the speakers and hits your ears that makes it extraordinary.

I met Joe Mardin when we were both students at Berklee. We happened to be sitting together in the back of a class on pop lyric analysis, and from what I recall we became instant friends. I think it was because we both have a dark sense of humor, but it could honestly be that we saw things the same way when it came to what we felt was great music.

Joe shared with me how his dad had this unique ability to hear the magic in an artist’s voice, and find the perfect EQ tweak, or finesse of the arrangement of a song, in order to bring out the best qualities of that artist. I hear this in every album Arif produced, from Aretha Franklin to Chaka Khan to Hall & Oates to Norah Jones. It’s there in the mix, and yet somewhat invisible, as it’s not so pronounced that it has a sound like some record producers have. It is simply what was needed to bring out what must come forward to make the song and the artist great.

When I think of Arif, I hear his work as one which draws upon influences from every corner of the world. This was what crossed my mind as, for whatever reason, I had this crazy idea to feature my friend Dimi Mahlis on Oud with big band for this composition.

For sure, Arif’s Suite Fraternidad was an album I really dug from my collection, and I expect it was somehow embedded deep in the recesses of my brain as I was writing The Mardini Effect. I don’t know where all my ideas come from as I’m composing and orchestrating. On first drafts, it is simply me playing with my toys and seeing what shows up. I knew I wanted to experiment with the Oud as a featured voice, to draw from a blend of modalities that would sit well with this instrument - although Dimi said to me later that some of my crazy octatonic scale passages were not so Oud-friendly!

This chart is difficult to play for everyone, as the fiery bursts at the ends of each section take some practice time to get comfortably under your fingers, especially with the unusual scales and odd time signatures I’m incorporating. I don’t necessarily start out thinking I’m going to write an “impossible-to-play” piece. I do like to challenge the musicians at times, while always attempting to give them something fun to play. I do love pushing the boundaries of what is possible – just to see if it can be done. Usually, I’m going for a feeling and the difficult passages are not necessarily ones that I am wanting to get 100% perfect. Rather, I’m just wanting to get the players on the edge of the precipice, almost out of control, yet still hanging on and keeping the energy of the section in the right zone, as they head towards whatever target I’m wanting them to move towards.

In the end, it’s the composition that tells me what to write. Much like a sculptor who sees a statue hidden within the stone, I use my composer’s tools to chip away at the exterior until I get to the core of the piece.

Outstanding solos from Andy Martin, Andy Suzuki, and Dimi Mahlis are throughout this track, and the band whips themselves into a frenzy!

— Lennie Moore

Essence

for Michael Gibbs

So, Lennie, MENTORS !!

———a continually growing list————

Such a long collection, over so many years - this has to be a conversational type ramble-attempting to start from earliest to latest - but they all overlap each other - so sticking to such a plan will not work.

The main man that comes first to mind however, is

HERB POMEROY –

whom I knew in a learning capacity, but also professionally, and as a dear friend. I think our first meeting was on the day I arrived in Boston to attend Berklee, from Rhodesia - January 9th, 1959 (a Friday) - on meeting and being welcomed by Bob Share and Larry Berk, (first names terms from the get-go) - and was invited to observe a recording session downtown. My first memories of Herb were studies with him - all of his famous three classes, but then, the composition class was a private lesson - Herb saw something in me beyond my earnest desire to be a jazz musician…which is all I was aware of - as if it wasn’t a choice I’d made myself. Very soon, it seems, I found myself in Herb’s famous Recording Band - playing trombone, writing - alongside a hand chosen selection of players at the school (student population in those days was about 250) - and included Toshiko Akyoshi, Arif Mardin - who’d already finished their studies but were still around and about.

CHARLIE MARIANO –

married to Toshiko at the time, was my first ensemble coach. Also in the band - Gabor Zabor, Gary McFarland - and a year or so later, Gary Burton. Gary and I became fast and lasting friends - he steered me more towards writing though I did still play trombone a lot - including with Herb’s professional small-big band when Gene DeStasio left to go on the road with Kai Winding. This band played at the Stables (local jazz club of the day) - every Tuesday and Thursday and the occasional Festival and outside gig - Sam Rivers was in the band - Boyo! was that an education.

One night, as we were playing my arrangement of KILLER JOE, Benny Golsen came in - he was one of the Stablemates, I guess!

Looking back (as I often do these days) - I do remember getting a lot of fabulous breaks - one of the first being - while still a student - having Gary invite me to write a composition and an arrangement for one of his early records - players included Phil Woods, Tommy Flanagan, Clark Terry, Joe Morello, John Neves…heady company for a mere student.

In my earlier teens, I already had a lot of mentor type connections with my beloved piano teacher

GORDON YATES –

who’d helped me discover jazz - Louis Armstrong groups, and later some more ‘modern’ music - Dave Brubeck, Gerry Mulligan, Shorty Rogers - for a while it was the West Coast scene that held my interest - when Charlie Parker died, and a radio programme played his music along with the announcement of his death - music new to me - my ears were pulled further east from California - and, as I was already a regular reader of Metronome and Downbeat jazz magazines, I discovered Jazz could be studied (officially) at sort of university level - so there I headed - failing my chemistry and physics studies at Pietermaritzburg, and concentrating more on the new jazz records from the USA my local jazz friends were turning me onto - I remember Chico Hamilton group with Buddy Collette, Jim Hall, there was a cello in the group Jeez! this was exciting - and then I read about

GUNTHER SCHULLER –

Man! he was so deeply steeped in the music and jazz world - playing French Horn in Metropolitan Opera Orch I think it was, but also on Gil and Miles collaborations, wrote jazz related books, composed, was a teacher –

I knew I had to get to the US!! So, in my first year in Boston, I contacted Gunther who agreed to take me on as a composition student - first bombshell he laid on me was Rite Of Spring. His 3 biggies for the 20th century at that time were Stravinsky’s Rite, Debussy’s Jeux, and Schoenberg’s Kammer Symphony.

Hearing the Rite is still a sort of essential need today.

I met Gunther again in 1960 - at the three-week summer school at Lenox (created by John Lewis with the MJQ in attendance) — Herb had suggested it to me - and I managed to gain a scholarship to attend.

Gunther taught a Jazz History course every other day - and the other main Class teacher was

GEORGE RUSSELL –

who was there with his band (Al Kiger, Dave Baker). I had heard about George’s Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organisation from other students at Berklee, and George taught an introductory version of it in his classes at Lenox.

But Lenox had other delightful and delicious treats –

J.J. JOHNSON’s

group came one night to play a concert - they had such a ball, John Lewis invited him to stay, hang out - beautiful place, great people, Massachusetts mid-summer) - and he did - together with his players, which included 22yr old Freddie Hubbard - and when Herb Pomeroy - who’s student band I was playing in (at Lenox) had to leave early for other commitments, Freddie took his place at the student concert; Connie Kay played drums - Wow!

After Lenox - J.J. joined Miles band - for about 18 months I believe - they never recorded that band to my knowledge - Hank Mobley there too.

MILES DAVIS –

well, with Miles it’s not just the first note !

He had it all, did it all –

I baulk at the mention, idea even, of perfection - where would you go what would you strive for after that.

Miles — I bumped into him once (in Village Vanguard), and was introduced to him twice (once by — Coryell at one of the Kix gigs, the other by — Labeque at John Mclaughlin’s Mediterranean Guitar Concerto premiere in Los Angeles), though never knew him or got to speak to him at any length - but his music is perhaps at the core of what I unconsciously seek - to figure out how to find and go beyond my own envelope !!

In later years, I quite often got to hang with the Weather Report band as I knew Jaco and would go back stage at his behest - had already known Joe a little - (he arrived in the US same time I did with a scholarship to Berklee, though stayed only about a minute ! ) - only to say Hi!, but asked Jaco to introduce

WAYNE SHORTER

to me - Nah Nah - he discouraged me - sort of like - Not Now discouragement.

But then - 2006 I think it was, Wayne’s Quartet came to Malaga (where I now live) and I asked John P to introduce us - after some 20 minutes of chatting - it felt like we’d known each other for ever - seemed so simple a connection –

He talked about the new orchestral/vocal (for Rene Fleming) music he was writing, and then - Ah! here’s the bus - he got on, they were off - haven’t had another chance…

As a lot of my class studies at Berklee - much as I loved them, did seem to have an overabundance of rules - (don’t do this, you can’t do that) - that I was ready to take on a reverse approach incorporating chromaticism into my tonal compositional exploits - tonal music was where I wanted to be. I had struggled to glean listening pleasure from Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto - I say struggled - because I felt I was supposed to be attuned to the relevant 12 tone rows of any 12 tone music I heard, in the same way I would know the II V I harmonic rules of, for example, a standard tune - but, in conjunction with George’s Lydian Concept, when I heard Leonard Bernstein in a lecture say that any music that used tones was (by definition) tonal - I was relieved, released and launched into a new direction - for life it seemed: each piece I would write from then on, I would have to reinvent (for myself) how to re-approach chromaticism - it seemed…..thanks George, and Lenny!!

And so - to UK.

On arrival there, I met up with Graham Collier - we’d been fellow students at Berklee, and he now had a band in UK - seven piece I think, which included a french horn. He dropped the horn and added me on trombone…so, within a week of arriving in this new land, I’d had a serious job!

Although Graham was deeply earnest in his connection to and about jazz - our ideas always seemed to only have a tangential connection. This gave…………

When he died - 2011 (?) - we still had stuff to sort out —

In Grahams bands, I got to meet and play with Kenny Wheeler, Harry Becket, Phil Lee, John Marshall, Sir Karl Jenkins –

and from them, merged into rehearsal bands with other musicians, especially the Saturday City Lit band - where I could get my charts played, play for others (Alan Cohen), and forge new connections. One day - a call came from Tony Russell (who’d also played at the City Lit band) to play for a club gig up north for Cleo Laine with the

JOHN DANKWORTH SEVEN.

My contribution passed the test, and from then on, I played for JD with his big band, film and studio session work, concerts, Ronnies, gig’s overseas (Belfast a few times!) - and had a fabulous time.

I know Graham was upset by my leaving his band –

Perhaps a leap forward would be a good move at this venture –

CHARLES IVES music, and the music of

OLIVIER MESSIAEN

has had a huge influence on me for years - and many others too, - certain pieces hold very special place in my makeup –

Debussy’s Trio Sonata (for Flute, Harp, Viola) — there is so so much composition, orchestration, melody, rich music stuff in just the first few bars - staggers me every time I hear it - and I often have to re-start listening to the piece three or four bars in.

It’s also became a bible for studying harp writing - which came in usefully for the commercial work I started getting in UK in those early years - another aspect Graham frowned on sadly!

Today, Scriabin’s Poem of Ecstasy still intrigues, Wagner’s Liebestrom - especially Jessye Norman’s version with Karajan’s (his last performance) - seems to be an everlasting source of inspiration - I checked out the score, but after barely a few pages, realised it wasn’t looking at those written notes that held the secret for me - it was more that I wandered how I could possibly achieve the devastating effect that music had on me.

Aretha Franklin’s “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman” - the version at the 2015———— has a similar effect - the answer (not knowing the question yet) doesn’t lie in the notes, so it’s not in any music how-to text books…

And there’s

LIGETI -

his piano etude book 3 No.16 (among others) does it to me.

And for a while there was (Dylan’s) THE BAND gave me a lot of pleasure - the groove of a piece became important and more prominent to me……..

As so now too - mentors appear out of the blue, as did –

HANS KOLLER –

he’d sought me out for a lesson - this was in the early 2000’s; after about 8 hours, sharing a single malt, it was I who’d had a lesson.

We went to a Joe Lovano/Hank Jones concert together once - and our sense of sharing was something deep, personal, and fulfilling without any verbal discussion about the concerts specifics, with perhaps only the barest inkling of eye contact a few times - make him someone I want, need in fact, to pass my music by/through, before I let it go further than me.

And now,

PABLO HELD –

Damn! - There are a few players who - as they play the first note of a piece, immediately grasp my attention, inexplicably - Gil Evans did it, Martha Augerish does it every time, Peter Erskine once - taking his cymbals out of its case at rehearsal - filled the room with a ping that seductively demanded attention - a mere tap.

Pablo Held’s music - indeed that of his trio - holds my attention intently. I can’t - not easily anyway - listen to a whole album in one sitting - each piece is like a substantial meal, needing digestion, contemplation, time to absorb and respond to in its own time...

And looking at the lead sheets - as Pablo is very organised that way - (I once asked him for a lead sheet - and within 10 minutes, he’d emailed the lead sheets for the whole album, and seemed pleased to offer it up to my and others scrutiny!!) - and the listening and looking barely make the sort of connections a lead sheet of a standard used to do to inform me of the piece –

There’s so much more to do yet…and I keep feeling in need of rest. Retirement is not a possibility, although the occasional longer lingering lie-in helps.

— Michael Gibbs Nov 2018

My first exposure to Michael Gibbs was a class he taught at Berklee College of Music (he was the Composer in Residence at that time). It was called something like Arranging for Large Jazz Ensembles, and he blew out my mind on the very first day of his classes.

My first two years had been filled with contemporary and traditional theory/harmony and by the end of my sophomore year, I found myself crossing my arms at concerts, over-analyzing everything, and not really enjoying music as much. In my junior year, his class and philosophy towards writing changed everything for me.

If Michael posed a question to the class, and your answer was anything technical or theoretical such as the Berklee method of harmony/arranging, he would ask, “What’s that? After you explained what it was, he’d say, “Oh no, it’s not that.” If you said “green” he would get really excited and say, “Tell me more!”

When analyzing a piece of music such as Eric Satie’s Gymnopédie, he spoke about getting to the essence of the composition. He would ask, “What is the essence of this piece?” The goal being: to discover what the core of this composition was about, and then building what you would do in your orchestration/arrangement from that essence.

Simply put, he got me out of my analytical head, and got me back to the heart of how music feels. The man saved my life.

Michael gave me back my soul, and this approach of finding a core concept, or essence, is a central part of my composing philosophy to this day. To create my scores for film and video games, I’m always seeking out a common thread or central thematic core that the music is based on, while supporting the story and the vision of my collaborators.

Since taking that course with Michael, I’ve discovered that my writing is at its best when it is a blend of the technical and theoretical aspects of composition, with what my intuition says is right in the way that my work feels. The final decision maker for me is my heart, but my head helps me get there.

Naming this track Essence - well, it had to be named that. This piece embodies the two sides of how I write, and I’m forever grateful to Michael for his encouragement and the part he played in helping me find balance.

While this piece has a very nostalgic feel, with its lovely melody in the high register of the trombone (played joyfully by Alex Iles), and its more traditional harmony akin to many jazz standards, it also has some unusual twists and turns.

When I was composing this piece, I was at my piano, thinking of Michael and experimenting with a certain melodic shape. Eventually, I ended up discovering that this melodic shape was a tone row (where no notes repeat, and every chromatic note is expressed in a single phrase). This got me all excited (yes, I like math). But in my excitement, I missed a note! It wasn’t actually a 12-tone row. After trying to find a place for the twelfth tone, it just never worked for me or sounded right – so I left it at an 11-note sequence. Sometimes, you just have to go with what you like and what feels right.

Each melodic phrase in both the A and B sections of this piece is built with different 11-note rows. What ties them together is the very traditionally sounding jazz chord progression. Even with the harmony being what it is, I think the melody has a quality of pulling the listener’s ear in different directions, and not really giving them something to hold on to…until the C section! At that instance, it lands clearly on a blues-influenced focal point and starts swinging in a “down and dirty” way that ties the whole form together.

— Lennie Moore

Smoke & Mirrors

for Don Grolnick

When he was young, his dad played "woodchopping" guitar in a little swing/jazz combo that would meet in his family's garage. Around that time his dad took him to see the Count Basie band, and the power and the swing of the group totally blew him away. Don would sit in with his dad's group, and his dad said that even as a teenager he was far and away the best player!

I know he did some formal piano training, but I think, as with many things, he did a lot of self-teaching. He would throw himself into the recordings of Trane, Mingus, Horace Silver, etc.

He started playing professionally while still in his teens, and I think that the players that he worked with influenced him greatly -- Michael and Randy Brecker, Barry Rogers, etc. FYI Randy Brecker knows a lot more than I about that early scene.

His pop/R&B was very influenced by Richard Tee, and he often said "I should pay him for all the licks I 'borrowed' from him. When he started to explore afro-cuban Latin music late in life, he did spend some time hanging and rehearsing with the giants of that music, namely Andy Gonzales and Milton Cardona.

— Jeanne O’Connor

I think every generation of artists has influences who embody all that they feel are the most profound aspects of being a creator. With jazz composition and arranging, there were extraordinary composers/arrangers like Duke Ellington, Gil Evans, Sammy Nestico, Bill Holman, Gene Puerling, Dave Barduhn, Neil Hefti, Don Menza, Thad Jones, Don Ellis, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Rob McConnell, and Bob Brookmeyer that inspired many of us to write for large jazz ensembles.

The consummate contemporary jazz composer and arranger in my world was Don Grolnick, hands down.

Lyrical melodies, deep harmonic sensibilities, great voicings, outstanding and adventurous development of form, along with his playing and production chops made Don stand out to me as the pinnacle of what it was to be a jazz composer/arranger in my generation. His compositions and collaborations with Steps, Michael Brecker, and many others are some of my favorite works of his: Chime This, Or Come Fog, The Four Sleepers, Pools, Nothing Personal – all tremendous compositions that have such depth and nuance. Every time I hear them it seems as if time mysteriously slows down, and my ability to listen and dial in to every nuance of his brilliant detail envelopes me.

In Smoke & Mirrors I took a lot of time to develop the harmonic language. The A section is blues-based, which reminds me of Don’s Richard Tee influence, but the harmonic structures are more ambiguous and suspended. The contrasting B section took the most time to create and refine, as it harmonically twists and turns, leading the listener through different tonalities until it winds back around to the beginning key center of F.

The C section acts as a long bluesy tag which leads into the solo sections and (in a very Grolnick-like way) the harmonic progressions during the wonderful solos by Nick Manson and Andy Suzuki are different than in the tune. These act as more of a development of what’s been established in the beginning of the chart. Their function is the same – a bluesy A section followed by a modulating and evolving B section. Each solo modulates to new key centers (D minor for the Piano and Bb minor for the Tenor Sax) and finds its way back to the primary key of F as we come back around to the tune, fully orchestrated with the full band.

I’m also continuing to play with form here. After the A and B sections, I modulate and restate the A section in a different key (D), followed by an extended C section in the original key, which turns into a piano vamp played brilliantly by Nick that fades out in a manner which I wanted to feel like Don jamming his way into heaven.

— Lennie Moore

Planetary Misalignment

for David Mash

So many people have mentored me, but I’ll choose just two to mention here. First was my guitar teacher Joe Fava. Joe taught me at a very young age that every note had to be beautiful, and that meant focusing on how the note began, how it rang, and how it ended. What color it was, how loud, and most of all how it fit into the larger phrase and context.

This so affected my playing, my writing, and much later in life, my sound design and work with synthesizers. Gary Burton also mentored me in several ways over my life and career. When I studied small band arranging with him, I learned from his musical example, and he also gave me the chance to listen and learn from my own writing, in fact, he forced me to be my own biggest critic - which still holds me in good stead today. He also mentored me in my role as a college leader, influencing my decision-making processes, and how I managed both people and projects.

These two mentors influenced me in quite different ways, but both forced me to listen, to be critical, and to hold high standards both for myself and for others.

— David Mash

David Mash was my Contemporary Theory & Harmony professor at Berklee. He had such a great way of clearly explaining harmonic concepts that have stuck with me to this day. His teaching has shaped how I think about how we hear music and all its component parts.

Dave is also a wonderful composer who loved writing in unusual time signatures. I loved playing his works, as well as going to clubs in the Boston area to hear his fusion band Ictus perform. The thing I remember most about his music is that his compositions had a flow to them, even with tricky time signatures like 15/16. This was different than many of the odd time signature tracks I had heard from other jazz artists. Dave’s pieces inspired me to experiment with time signatures while striving to get the groove to feel organic.

Planetary Misalignment, in honor of Dave, is written in 4/4+3/4 time with some transitional phrases that are sequences in 3/4. I also put a little “salsa on my eggs” in the arrangement, by writing in a more Latin Jazz style (especially on the B section). I have no idea how that section came to be. It just popped into my head to go full-on Salsa there with the horn lines and percussion. The arrangement even includes a moña section (a build-up of riffs in the horns) to give it a traditional bit of fun. The bass line, which I’m playing, is hard to play well – especially as I’ve been mostly a composer/orchestrator for decades, versus focusing on being a performer. But it is an integral part of the overall feel of this tune, and it’s very much in line with keeping the flow as a nod to Dave.

Dimi Mahlis and Andy Suzuki tear it up on their respective Electric Guitar and Alto Sax solos, and the horns are killing it throughout this track.

— Lennie Moore

Two Peas In A Pod

for Andy Suzuki and Nick Manson

I’ve been fortunate throughout my life to have had many teachers, colleagues, and friends as mentors. These are individuals who taught me not only about the mechanics of playing instruments or music theory, but deeper lessons in life. My earliest ‘guide’ was Johnnie Jessen who taught me not only how to play the saxophone and flute, technically, but gave me an understanding about musicality, humility, self-confidence, and was a great example of someone who remained passionate into his 90’s. Dave Press, my piano/theory teacher inspired me to ‘think’ and filled my toolbox further, never letting me forget to have fun. I had three fantastic music teachers in school, Pat Seymour in middle school, and later in high school Ed Peterson, and the renowned Hal Sherman. Each had their unique style of teaching but what they had in common was to recognize that I was a very self-motivated kid, so no need to push, just adjusting my course here and there when needed. I cannot overstate how important they all were in my early growth.

In my professional life mentorship continued with colleagues and friends, usually both, who helped me continue to mature as a musician and taught me a lot about the music business. While this list would get way too long and includes many well-known players, I would like to mention just a few that I’ve been making music with for over 30 years, Nick Manson, Lennie Moore, Dean Taba, Ken Lasaine, and Jim Wiggins. Not only are they dear friends but along the way I’ve learned a great deal about music and its history, to never stop learning, to never underestimate where inspiration can come from whether drawing from other art forms, mathematics, or just about anything else! Above all my mentors have inspired me to continue growing throughout life and have taught me, no matter how difficult or trying, a life in music is an honorable service to others and to myself. Following your own path has unimaginable rewards, you just need faith in yourself…and some help along the way!

— Andy Suzuki, 1st Alto Sax, 1st Tenor Sax, Flute

Students and some of my followers frequently ask me, "How did you develop your music career?" I tell them the following –

When you listen to me play or my recordings, you are listening to the culmination of knowledge that I obtained and synthesized from three "classifications" of mentors.

Educators, ranging from private lessons to public schools, and colleges, including clinicians.

Musicians I have interacted with from the beginning to the present day (musical peers and me functioning as a sideman).

Musicians that I have never met, but whose recordings and live performances I hold close to my heart.

Educators - my first formal music lessons were on a Lowry home organ which I hated with Nora Butler in her trailer home. She was quite elderly at the time, but she knew music theory in her sleep and drilled me with workbooks. I was about 8 years old at the time. Dave Press was an incredible jazz bassist in the Seattle area during the '70s. Interestingly, he was a jazz theory giant and played the piano with a touch very comparable to Bill Evans. Peter Leder was the assistant conductor to the Seattle Symphony, and a technically brilliant pianist that drilled me in Bach. A lot of Bach! Ed Peterson was my high school band director, who introduced his students to jazz via the greatest composers and arrangers of the era, we never played easy arrangements. I really learned a lot about running a band from him. Rich Matteson, a professor at NTSU (UNT) was a clinician at the Stan Kenton clinics I attended in the late '70s. He played euphonium, trombone, piano, and more. He would always give me extra time regarding arranging techniques and he introduced me to the music of Lyle Mays who was a student of his at the time. Dave Mash taught me chord scale theory and arranging, and I played in his ensembles at Berklee College of Music. I love his music. There are many others, this is not a comprehensive list by any means. I wish I could list them all.

Musical peers and sideman work - Saxophonist/composer Andy Suzuki are approaching 45 years of making music together. Andy taught me how to transcribe. Lennie Moore and I met in high school as arrangers for a Seattle-based singer in the late '70s. Both Andy and Lennie were in my first band which played our original music prior to turning 21 years old! Drummers Gerry Gibbs (who taught me how to listen and play at the same time) and Ian Froman (who taught me how to dig in and swing), both players I met at Berklee, are extremely influential regarding my approach to music and improvisation. Donny Marrow taught me how to navigate the music business and publish my works. Tim Noah, a PNW-based composer, and songwriter, as well as gospel artist Roby Duke were huge influences. Bassist, Dean Taba. And John Patitucci was enthusiastically gracious with me, playing on two of my recordings. Also, Michael Lord taught me how to engineer recordings. Again, this is just the tip of the iceberg. I wish there was more space to list everyone.

Musical Mentors that don't even know they influenced me - Lyle Mays is really huge for me. I bought Pat Metheny's album, "American Garage" because Rich Matteson told me to check it out. Claire Fischer, Bill Evans, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett, Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Herbie Hancock, Dexter Gordon, Thad Jones/Mel Lewis, John Coltrane, George Cables, Steve Huffstetter, Bach, Debussy, Satie, The Beatles, Elton John, Christopher Cross, Bob Wilson (Seawind), Jeff Lorber, Jeff Beck, Jan Hammer, Thomas Dolby, Stevie Wonder, and Michael Jackson. Again, this is not even close to comprehensive.

Of course, my parents and immediate family were all mentors and supporters, too, especially when times were not so easy.

— Nick Manson, Piano, Fender Rhodes, Minimoog

I met Andy Suzuki and Nick Manson in my senior year of high school. Our collaborations and creations over many decades of friendship have been more than joyful. We share a passion for great performance and have challenged each other to push boundaries in our respective work, individually and in joint ventures. They have motivated and inspired me to continually strive for excellence in all that I do.

Andy and Nick have a very special bond, which shows when they are playing and performing together. I can see it in their eyes as they look at each other when they play – a look from Nick that resembles a dare…for Andy to top what he just played, and vice-versa. It makes me smile every time I see them play, as I understand it to come from not necessarily a competitive perspective, but rather a nudge towards something greater and deeper.

When I think of this aspect of who they are, this is totally where my title of Two Peas In A Pod came from. I wanted to create a piece that featured both in their element, playing off of each other. The sound of Nick’s Fender Rhodes and Andy’s Flute is reminiscent of the many times we played together as teenagers in The Shack - Nick’s studio in his home where he grew up. This was simply a small out-building where we had a setup for jamming together, playing each other’s tunes as well as standards and transcriptions. Another element of this specific Rhodes/Flute combination reminds me of Chick Corea’s wonderful album, Friends, with Chick playing Fender Rhodes and his long-time collaborator Joe Farrell playing Flute – an equally similar great pairing.

The Samba feel in this piece is a choice that really works with this overall sense of joy I feel when I reflect on our friendship and mentorship to each other over the years. These are two of my best friends, and I can’t think of a better way to honor them, than to give them a vehicle to nudge each other, and me smiling (and playing) along with them.

— Lennie Moore

The Kid

for Ken Kraintz

I had the extreme good fortune to have had several pivotal mentors in my musical career. Certainly, the great instructors and directors at the community college and college/university level I encountered stand out and were extremely important, but there were two teachers that actually got me interested in music, and then in music education that I have to acknowledge.

The first is Bill Johnson, my band director at Coontz Junior High School in Bremerton Washington. Bill was a veteran US Navy musician that ended up teaching band in my hometown of Bremerton. Although he never spoke of his training, he was an accomplished jazz drummer before he became a teacher, with lots of connections through his stint at the Navy School of Music and playing in various USO tours around the world. He introduced me to jazz by having me accompany him to his weekly Elks Club jazz band rehearsals and play trumpet with all the old retired musicians that made up the group. They needed a trumpet player and I was it. Every Tuesday night he would pick me up at my house and take me to the club and I’d play from 7:00 pm to 8:00 pm with the band, and then they would begin the adult activities like smoking cigars and drinking large amounts of bourbon and I would walk home. One time he bought me a concert ticket to hear a professional trumpet player he knew and wanted to introduce me to. The sold-out concert was at our junior high school auditorium, which was huge and seated about 1500 people. I didn’t know the performer, but after the show Bill took me backstage and introduced me to his friend – Louis Armstrong. It was literally several years after that event that I realized what had happened.

The second person that influenced me a great deal was my high school band director, Bill Bissell. Watching him work and observing the respect he received made me want to be just like him. He was not a fantastic performing musician by any means, but he could teach better than anyone I ever knew. He had a way of communicating in a non-judgmental, positive manner that I tried to emulate throughout my teaching career. In other words, take students from where they are and get them to a higher plane, while having fun and enjoyment along the way. He had a great sense of humor and was totally selfless with his time and talent. His greatest sense of pride came from his student’s success, not his own, and we all tried to do our very best to live up to his expectations. Even after I began my career as a band director, I never considered him as a peer, but as someone who I always would look up to. People like that are truly the ones who will stand out in my mind forever.

— Ken Kraintz

Ken was the director for all the arts in the school district where I grew up in Everett, Washington. He was an innovator in vocal jazz and creator of a choral ensemble (plus a rhythm section) at my high school known as the Del Sonics, which performed throughout the community and in vocal jazz festivals across the Pacific Northwest.

His compositions and arrangements were clean and fun to perform, and he was a tremendous conductor and teacher who could work with students having various singing abilities, shaping their phrasing and articulation until the ensemble was tight, in-tune, and expressive.

My involvement in the Del Sonics was as a member of the rhythm section. In my freshman year (I was playing only Trombone at the time), Ken approached me and said that the electric bassist was graduating, and that he thought I would be pretty good at it. He offered to loan me the school’s Fender Precision and said auditions were in two weeks. I took on the challenge, learned the basic fingerstyle playing technique, played through all of Ray Brown’s Bass Method book, did the audition (sight-reading written notes and doing “walking” lines based on chord progressions), got the gig, and found an instrument that resonated with me with much more passion than all the brass instruments I had played since elementary school. In essence, Ken had introduced me to my “other wife.”

The Kid is my tribute to Ken and his influence on me and so many other students who were the recipients of his tutelage, encouragement, and joy of music. I wanted a feature piece for the Fluglehorn (Ken was a Trumpet player), where Andy Gravish masterfully performs the solo part, that had a beautiful bossa feel and lots of dynamic color - like the woodwinds behind Andy’s solo, to piano/bass figures which propel the end of the harmonic progression back to the beginning of the form, to Nick Manson playing his beautiful solo on Piano, to the shout chorus where we bring a long build-up to its climactic point and wind down to the unresolved ending.

Ken’s positivity, leadership, guidance, and great musicianship has meant a lot to me. As a teenager feeling doubt about my place in the world, Ken introduced me to a creative community and gave me a home where I could express myself and find joy.

— Lennie Moore

Intentionality

for Toshiko Akiyoshi

I think I was about 16 when I signed up for a summer composing workshop called Centrum at Fort Worden State Park in Port Townsend, WA. For whatever reason, only three people signed up for the jazz composition program, and the guest artist for that year was none other than the legendary Toshiko Akiyoshi. It was such a treasure to have so much one-on-one time with her, and the memory of that encounter has remained an indelible one for me.

We all had to write a piece for big band, to be performed at the end of the week by a professional band under Toshiko’s direction. As she was looking over my score, she pointed to a particular measure in the sax section and asked me, “Why did you write this?” Being a teenager, I responded with a stock, “I don’t know.” She continued to press me with, “Why is this here? What is the reason that this is here?” I thought about it for a bit and said, “Because I like it,” to which she responded, “Good enough.”

She followed this comment with her philosophy that there must be a reason why something goes on the page when composing, followed by a review and assessment of why something should stay on the page. She called this Intentionality.

This idea had such a profound impact on me that to this day it is a fundamental aspect of my approach to composing – that an act of creation should have a clear intention as to why it exists, a reason for it being there, and a confirmation for why it was chosen to remain in the final version of any work.

— Lennie Moore

Band Member Statements

Billy Martin

David Baker, jazz educator and Indiana University professor. His teaching approach was highly organized and methodical, but his music was emotional and inspiring.

John Eaton, my composition teacher at IU. John loved opera and microtonal music (I did not), but he was open to all kinds of music. Early in his career he played in an avant-garde jazz group and his guidance (even on a big band chart) was always insightful.

John Von Ohlen, jazz drummer. He worked for Woody Herman and Stan Kenton, then returned to the Indianapolis area for the rest of his life. I played in his big band there many times--he was the most swinging drummer ever.

Phil Woods. When his album Live at the Showboat came out, I was hooked. I saw him live once, at the Bluebird in Bloomington Indiana. I always tried to sound like Phil on alto.

Dmitri Shostakovich. His fifth symphony was an early inspiration, as were his perseverance through adversity and his dedication to his craft.

Thomas Newman. I wasn’t initially a fan of the minimalist style, but his music really grew on me. I scored a couple of video games based on his movie scores and I learned a lot from studying his music. I’ve met him a few times and he seems like a down to earth, genuine guy.

The Beatles. The first inspiration, they set me on a musical path at a very early age.

— Billy Martin, 2nd Alto Sax

Phil Moore

My mentors have always been my family and friends. My wife Dana and son inspire me daily to do and be the best. With barking dogs, joyous laughter and dryer sheets shoved into pockets or sock, they are my greatest mentors.

Craig Holt was my first boss in the science for dollars business. Craig taught me to compassionately observe my strengths and weaknesses. He showed me how to use my strengths and how to develop skills to bolster weaknesses. Dr. Holt was a great physicist, boss, Buddhist and friend. We inspired each other to seek great teachers to explore our interests. For him it was Tibetan Buddhism and Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche. For me it was the musicians around me and Don Raffell.

I studied improvisation, sax, clarinet and flute with Don Raffell, a brilliant musician with a recording career spanning from the 1940s into the 1990s. He taught me that we are spontaneous composers, that melody always takes precedence, and “how you say what you say” is important. He urged me to honestly listen, play with logic, use economy and emotion. He would say “Don’t say a bunch of spinach, car tires, and garbage!” I play with the same warmth and ornery objectivism he taught me with.

— Phil Moore, Bari Sax, 2nd Tenor, and a bunch of squirrely doubles

Eric Miyashiro

My dad, who I consider my first mentor, was a local trumpeter gifted as a multi- instrumentalist and an arranger. My house was full of musical instruments, and he would play me many different genres of music on his turntable all day. So, music at first was my “toy”, and he never encouraged or discouraged me to take up an instrument, he just let me be with my discoveries.

I was born and raised in Hawaii, a paradise indeed, but somewhat of a musically conservative place. So when I got to middle school, teachers tried to force me to take lessons from classical trumpet teachers, and told me that “stage band was bad for your chops” and also I was playing the wrong way, and if I didn’t take a formal lessons with a teacher, I would not be able to play past high school…… (I am proud to say I am still working almost every day at age 60!)

My dad would not intervene, and he did not give me any lessons, but always told me to play what I enjoyed, which was everything music, so I just played in any and all musical opportunities I could find. I was free to make all the mistakes and discoveries, and find the courage to figure out problems on my own.

’Till this day, I have not had any formal lessons, but I was lucky to have met and played with many of my heroes, Bobby Shew, Maynard Ferguson, Buddy Rich, Jerry Hey, to name just a few. But I would definitely say that my dad, who never once told me what to do, is my mentor. (and was my biggest fan….)

— Eric Miyashiro, 2nd Trumpet

Tim Larkin

There are so many mentors throughout my career that have inspired me that it seems unfair to only mention a few.

The first that comes to mind is my trumpet professor at Cal State Hayward (now Cal State East Bay), Marv Nelson and my first private trumpet instructor Joe Fascilla.

They taught me not only about trumpet playing and the importance of musicianship, but how to balance that with life and relationships. At times when I thought only my playing would define me, they showed me that the piece of metal tubing called a trumpet is just that, a piece of tubing and it's what's behind the mouthpiece that's so much more important.

It's tough to define some influences as mentors although sometimes the freedom and autonomy that I've been allowed in several of my work experiences including composer positions at Valve and Cyan have allowed me to grow working in situations far beyond what I thought I might be capable of. It's not always an individual that teaches but sometimes the environment you find yourself in. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have been in multiple creative situations with people putting trust in what I do to inspire learning from each experience.

— Tim Larkin, 3rd Trumpet

Andy Gravish

All our lives, we as musicians, are constantly inspired by a multitude of mentors. To define my basic mentors, I must first acknowledge my private teacher from my early years,

Mr. Bobby Price.

Mr. Price was a retired U.S. Naval musician / trumpet player. He taught me the importance of discipline and respect for the instrument and music, as well as introducing me to the music of Jazz Greats such as Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Louis Armstrong.

Throughout the many years of taking lessons with him, the greatest advice Mr. Price imparted to me was simple: "Stay humble!" I strive to live up to that every day.

My other fundamental mentors were from my student days at Berklee College of Music. Namely, Jeff Stout, Louis Mucci and Mike Metheny.

Jeff was basically the reason I decided to attend Berklee. He took me deep into the language of Jazz in the three years I studied with him.

Louis was a living legend and such an iconic figure. Playing duets with him weekly was an experience beyond words.

Mike was practically my Big Brother in the sense we were closer in age, and we shared so many wonderful ideas and times together during our lessons.

Of course, the list can continue, but I feel particularly indebted to these Gentlemen who made me the musician and person that I am today.

— Andy Gravish, 4th Trumpet

Alex Iles

My big mentors...

My family-- dad, mom and sister. I grew up in a loving environment of support, exploration, independence, honesty, inspiration, perspective, encouragement, and lots of laughing.

Musical: Art Farr [who started me on trombone], Roy Main [my primary trombone teacher, introduced me to the idea of becoming a professional], Gary Foster and Bill Green [uncompromising woodwind artists who made me see things differently and expand my perspective about music and my instrument], Vince Maggio [jazz pianist and improvisation teacher at the Aspen School of Music introduced me to the things I needed to address to play changes and good time feel] Dick Nash, Alan Kaplan, Bill Reichenbach [studio trombonists with incredible sounds, versatility and class], Tom Kubis [big band leader, incredible and playful musician who hears the good in everything he hears], and all the musicians I have ever worked and played with, across the US, abroad, on the road and especially here in LA!

Education...Coach Giambronne, my first little league baseball coach, Mr. Tipton, my driving training teacher, Mrs. Kincaid, my 8th grade English teacher, Mr. Fountain, my high school Physics teacher, Sonya Packer, my college Speech teacher and Renaissance woman, Mark Plant, my Public Finance Economics professor who explained complex subjects with simplicity and empathy.

Life; My wife, Sandy, who teaches me more every day than just about any person, book, class, website, Ted Talk or seminar!!

— Alex Iles, 1st Trombone, Bass Trombone, Tuba

Andy Martin

My first mentor was my dad, David Martin. He still plays the trumpet. He was such a positive influence on my brothers and I and always played such tasty solos.

He got me my first teacher, Robert Simmergren when I was in the 8th grade. Other mentors were Charlie Shoemake, Roy Main, Rick Hahn who all were great teachers.

I looked up to my idols, Carl Fontana, Frank Rosolino, Dick Nash, Lew McCreary, Bill Reichenbach, JJ Johnson and many more.

— Andy Martin, 2nd Trombone

Jim Lutz

I have been inspired by so many amazing mentors throughout my career. Those include my teachers Dr. Robert Lindahl and Bill Watrous, along with JJ Johnson, Wycliffe Gordon, and Fred Wesley. I have also been greatly inspired by the outstanding Alex Iles and Andy Martin, with whom I am humbled and honored to have played on this project.

— Jim Lutz, 3rd Trombone

Ken Lasaine

My first serious guitar teacher, or I should say the first teacher I got serious with; Daryl Caraco, helped me transcribe my first jazz solo - “Wholly Cats” by Charlie Christian. After I learned it perfectly he said, “Great, let’s play some blues … and don’t play any of that Charlie Christian solo”. Speaking of Blues, I played with Big Jay McNeely for a while. At one rehearsal he got really upset with me. I was changing up my rhythm/comping parts a lot. He stopped the band, looked over my way and told me to never change my vamp pattern until the form starts over again. The two lessons here, for me, are 1) It’s jazz – improvise. 2) Be true to the intent of the song.

All of the musicians involved in making this record are my mentors. Many of them I grew up playing with and learning alongside of. The rest of them I grew up listening to, hoping that I could one day play alongside. The best piece of advice that I got, either from these guys that I know or from what I could glean via listening to the ones I hadn’t yet met, was to always strive to be myself, be creative and be authentic.

— Ken Lasaine, Electric Guitars

Dean Taba

Joel DiBartolo was the person I most consider a mentor, not only as a bassist but as a collaborative musician and educator.

Tagging along with him to gigs and rehearsals were the best lessons I could have asked for. From eating in the NBC commissary with the Tonight Show Band to driving together up to Half Moon Bay to hear Joel with Denny Zeitlin to carrying amps up the flight of stairs behind Le Cafe to watch him with the Cal David Blues Band, Joel was a tremendous wealth of knowledge and experience. Not only hearing him play but watching him resolve inevitable conflicts between musicians were such tremendous lessons for me.

Many nights were spent hanging out playing a game of “Where is the form?” as we’d needle drop on LPs and race each other to figure out where in the form the music was. Another game we played, often on road trips was to name a venue, bandleader or musical theme, then take turns selecting a “fantasy band” that would be the best combination for the occasion.

Joel always played whatever the music called for and ALWAYS made the group sound better than they ever had. He is dearly missed and I think about him every time I make or teach music.

— Dean Taba, Acoustic Bass

MB Gordy

My very first influence was listening to The Beatles and bands from the British invasion. At that point I started playing the drums and finally at the age of 15 started taking drum lessons all through high school with a teacher by the name of Buddy Isackson. He was the happening drummer and drum teacher in our area and he pretty much introduced me to the world of jazz. Thru that I got into Buddy Rich and big bands. All the while, I was playing in top 40 and rock bands and was into the music of Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, etc. and then moved to James Taylor, Carole King and on and on.

When I went to college I studied at Towson State, where I then got into the world of percussion: Timpani, mallets, Classical music, as well as studying in jazz Band with Hank Levy who was way into the odd time signature stuff and turned us all on to the music of Don Ellis. While at Towson State College I heard Chick Corea’s album Light As A Feather and that changed my life yet again.

After I left Towson State and was out of school for a year I went to Glassboro State College in New Jersey (now Rowan University) and really dug in to the classical/avant grade world. I studied with Joel Thome, who was really the first “real mentor” I had ever had. He changed everything and introduced me to so many things besides music. Books, architecture etc. and while there I also studied and played in the big band under the direction of Manny Album. Because of Manny I was able to play with a lot of name artists from NY who he knew and would get to come down and play as guest artists with our big band.

Also while at Glassboro, I heard the Paul Winter Consort and another group named Oregon, and the percussionist in that group was a man named Colin Walcott who totally flipped me out. It was the first time I had ever heard Tabla live, as well as all the other instruments he played, and then I was hooked on the world of ethnic percussion.

From there, Joel had recommended that I go to California Institute of the Arts and study with John Bergamo, who was a world-renowned ethnic percussionist. So, I went there to study with him and then got into the African Ensemble (Ghanaian Music), the Javanese and Balinese Gamelan ensembles, and I studied Indian music with Taranath Rao and Amiya Dasgupta. That experience at CalArts is what shaped me and my career for the rest of my life. It was thru John that I was introduced to the world of film music and was introduced to Leonard Rosenman, who got me on my very first professional gigs in Los Angeles, and my very first film scoring session.

The rest is History!!!!!

— MB Gordy, Percussion

Mentor Statements:

SMOKE & MIRRORS

Jeanne O'Connor

PLANETARY MISALIGNMENT

David Mash

TWO PEAS IN A POD

Andy Suzuki

Nick Manson